Study finds Toxic Cocktail in Synthetic Turf

Hundreds of synthetic sports fields in Sydney could be exposed to what independent testing has described as a “toxic cocktail” of chemicals.

Independent testing of a synthetic sports field in Sydney has found a “toxic cocktail” of chemicals capable of killing marine life and raising serious questions about the safety of those who play on it.

Community Science Group, AUSMAP carried out the test on a field belonging to an unidentified Sydney Council. It believes the results are indicative of hundreds of synthetic sports fields across the country.

“It is like a cocktail of chemicals sitting on these fields that we are potentially exposed to,” said research director, Dr Scott Wilson.

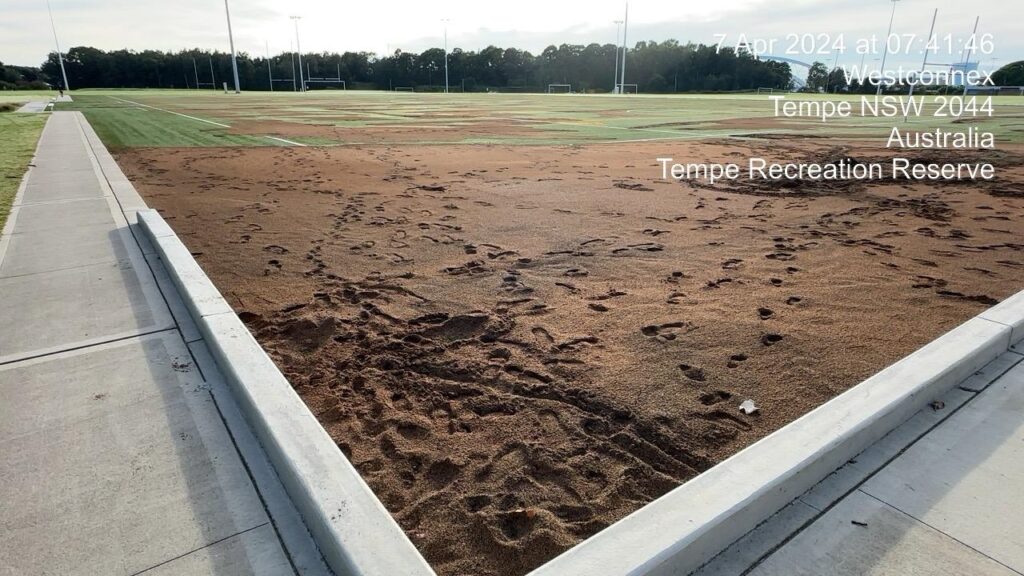

The group’s tests focused on what is known as “crumbed rubber,” a substance sprinkled across the field to provide support and replicate the play of a proper field. The crumb, however, is made from old, shredded tyres which by-in-large have been imported.

“In our study, where we looked at the rubber particles … We are able to find that heavy metals in particular were elevated,” he said. “Things like zinc, copper, arsenic lead are all present.

“Other compounds like PFAS and PAH compounds were also found. There was a cocktail of chemicals there,” he said.

PFAS is an umbrella term for thousands of man-made chemicals designed not to break down. The United States Environmental Protection Agency states, “studies have shown that exposure to some PFAS in the environment may be linked to harmful health effects in humans and animals.”

PAHs are another class of chemicals found in tyres. The British Journal of Cancer states PAHs have shown the capability to “cause mammary cancer in rodents.” While a separate 2022 study describes PAH’s ability to induce “troubles in female fertility.”

Other studies found traces of the crumb in the saliva of players, opening a potential path for the chemicals into the blood stream.

With sports fields often flowing into creeks and rivers, AUSMAP conducted its own independent lab tests to examine the impact on marine life and the broader food chain.

“Within a couple of days, the levels of chemicals in that water where the rubber crumb was sitting … was killing our crustaceans (and) our small little invertebrates that are the backbone of our eco system,” Dr Wilson told Sky News.

“We were finding the chemicals present are immediately killing these animals because they are so highly toxic.”

The issue of crumbed rubber has led the European Union to begin the mammoth task of removing some 100,000 synthetic turf across 30 nations over the next eight years.

It intends to replace the recycled tyre crumb with coconut or cork.

“What I can say is, be aware of the rubber granules and keep as far from them as possible. This is definitely what we are doing in Europe,” said Mercedes Marquez-Camacho, from the European Chemicals Agency.

As well as the effect on humans, the agency is equally worried about the spread of the tyre granules into the environment. And while they look to be rubber, the synthetic substance is actually made of plastic.

It believes somewhere between one and five percent of all granules are lost each year, a figure it estimates to be a staggering 16,000 tonnes annually.

“Your children, when they come home, they bring the rubber granules with them. And these rubber granules are made of materials that are carcinogens and also may damage the fertility and our hormonal systems,” said Ms Marquez-Camacho.

“And then when we think about the microplastics and the pollution of our environment and the understanding that there is in the scientific community that we all of us, we are drinking water that is contaminated with the microplastics, we are eating food that is contaminated with microplastics. These microplastics (are) in our bodies, and the real truth is that the scientists do not really know to what extent these microplastics may affect the human health. I would say that’s a worrying situation,” she said.

A 2022 report compiled by the New South Wales, Chief Scientist, Professor, Hugh Durrant-Whyte declared, “there is insufficient information and a lack of standards about the materials and chemical composition of synthetic turf.”

The chief scientist recommended following a ‘learn and adapt’ approach.

The report, which some believe has gone under the radar as a consequence of the 2023 election notes an increase in the state’s fields “from approximately 24 in 2014 and 30 in 2018.” to around 180 at the time. It’s now thought to be around 200 and growing.

While the European Union is moving away from the crumb, a new draft report for decision makers called “Synthetic Turf in Public Open Space” lays out the pros and cons of the fields, despite stating “research has suggested that biological pathogens, toxic chemicals and micro-plastic ingestion are all risks to human health that are associated with synthetic materials”.

It also notes the carpet itself – made up of forever chemicals – has a life span of eight to 10 years before needing replacement.

The European agency was careful to avoid any criticism of Australian councils and state governments, but did say in regard to the crumb, “we do know there are toxic chemicals in there, so spreading toxic chemicals in the environment, it doesn’t look like the best way to proceed.”

AUSMAP’s Dr Wilson made it clear there is no direct link between the product and cancer in humans but is eager for a moratorium until scientists can investigate the impact of chemicals.

“We just haven’t done enough studies yet to understand the potential ecological impacts of what this material is causing,” he said.

“There’s not clear evidence of potential human health effects at this stage, but having said that, we should take a precautionary approach and not expose ourselves to that in the first instance.”

This article was published by Sky News Australia on 7th May 2024. Click here to view